This afternoon as I investigated the various mysterious folders on my old computer labelled “Miscellaneous” and “to sort” I found a foreword I wrote for the website www.unseenhistories.com to accompany their beautifully designed web version of part of the silk chapter in my 2021 book Fabric. It made me smile to remember thinking of the silk moth I saw in Lyon as my own white rabbit.

Lucas Cranach’s matching portraits of Henry IV of Saxony and Catherine of Mecklenburg, showing the new fashions both for full length portraits and for clothes cut to show the expensive silk peeking out from underneath.

“When I was writing Fabric, I found myself pushing back the planning of the silk chapter until almost the end. With bark cloth and sackcloth and linen and cotton and the others, there were clear and burning questions in my mind that I was excited to find the answers to. With silk, I was initially less interested in it because it was so obviously luxurious. And having lived in Asia for more than a decade, I had a vague (and as it turned out totally unfounded) feeling that I probably already knew much of what I needed to know.

But then I went to Lyon, historical centre of France’s silk industry, and I met a silk moth for the first time. It looked like a fluffy white rabbit and like the white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, it was the moth itself that would be my guide into the rabbit hole of research into, and discovery of, the extraordinary fabric that is silk. In the end it was a journey full of unexpected turns and discoveries. And it was a journey that began where it needed to begin, with a sharp sense of compassion for all the creatures that die to give us silk.

Fabric is the third in what’s turned out to be a trilogy of books about the histories of small, bright and (usually) lovely materials. And when I was researching each of the books I found doors opening into worlds of history and struggle and beauty and symbolism, and every time it was a surprise.”

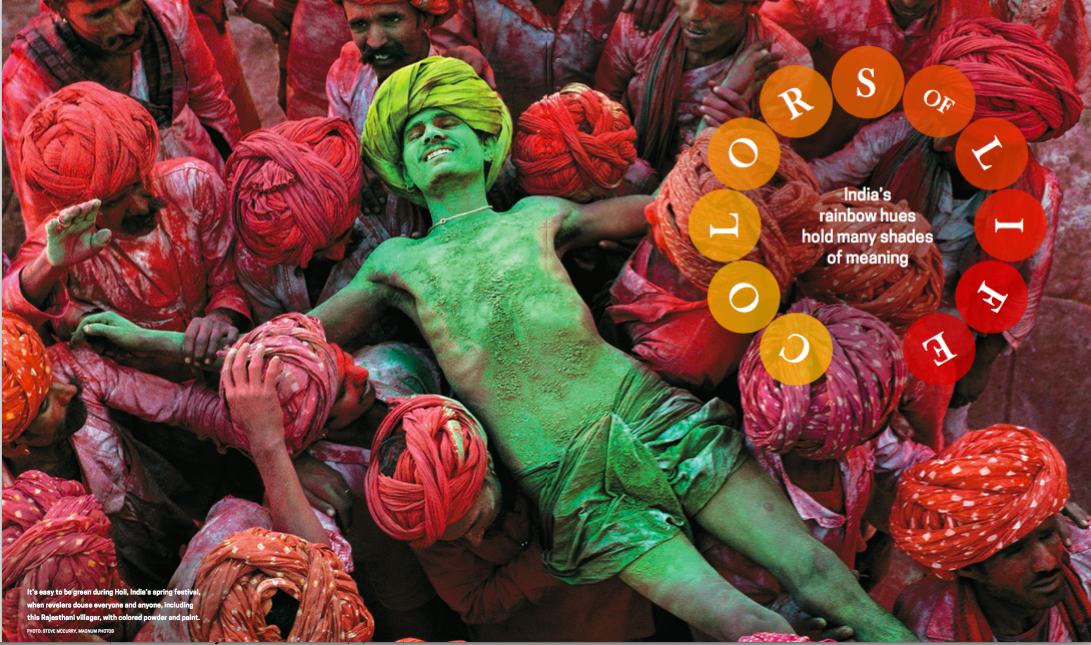

Holi represents the arrival of spring and the triumph of good over evil. It is also said to be the enactment of a game the Hindu god Lord Krishna played with his consort Radha and the gopis, or milkmaids. The story represents the fun and flirtatiousness of the gods but also touches on deeper themes: of the passing of the seasons and the illusory nature of the material world.

Holi represents the arrival of spring and the triumph of good over evil. It is also said to be the enactment of a game the Hindu god Lord Krishna played with his consort Radha and the gopis, or milkmaids. The story represents the fun and flirtatiousness of the gods but also touches on deeper themes: of the passing of the seasons and the illusory nature of the material world. My father’s funeral was three months ago last week, and as several friends have told me strictly, it’s about time I posted HIS eulogy to go with my mother’s. His funeral was on December 9, and he died on November 26,

My father’s funeral was three months ago last week, and as several friends have told me strictly, it’s about time I posted HIS eulogy to go with my mother’s. His funeral was on December 9, and he died on November 26,